Description

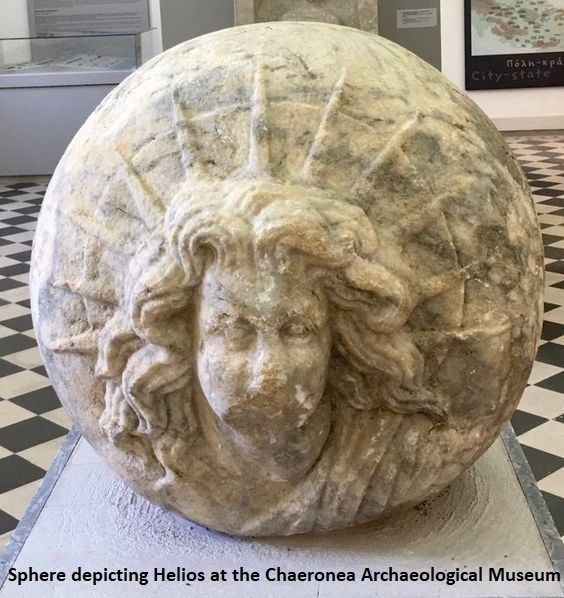

| ITEM | Architectonical fragment of Helios |

| MATERIAL | Marble |

| CULTURE | Greek, Near Eastern |

| PERIOD | 323 – 31 B.C |

| DIMENSIONS | 130 mm x 140 mm x 170 mm |

| CONDITION | Good condition |

| PROVENANCE | Ex Art dealer, acquired from European private collection prior to 1990s |

| PARALLEL | Sphere depicting Helios at the Chaeronea Archaeological Museum |

Helios, (Greek: “Sun”) in Greek religion, the sun god, sometimes called a Titan. He drove a chariot daily from east to west across the sky and sailed around the northerly stream of Ocean each night in a huge cup.

In classical Greece, Helios was especially worshipped in Rhodes, where from at least the early 5th century BCE he was regarded as the chief god, to whom the island belonged. His worship spread as he became increasingly identified with other deities, often under Eastern influence. From the 5th century BCE, Apollo, originally a deity of radiant purity, was more and more interpreted as a sun god. Under the Roman Empire the sun itself came to be worshipped as the Unconquered Sun.

The Hellenistic states of Asia and Egypt were run by an occupying imperial elite of Greco-Macedonian administrators and governors propped up by a standing army of mercenaries and a small core of Greco-Macedonian settlers. Promotion of immigration from Greece was important in the establishment of this system. Hellenistic monarchs ran their kingdoms as royal estates and most of the heavy tax revenues went into the military and paramilitary forces which preserved their rule from any kind of revolution. Macedonian and Hellenistic monarchs were expected to lead their armies on the field, along with a group of privileged aristocratic companions or friends (hetairoi, philoi) which dined and drank with the king and acted as his advisory council. The monarch was also expected to serve as a charitable patron of the people; this public philanthropy could mean building projects and handing out gifts but also promotion of Greek culture and religion.