Description

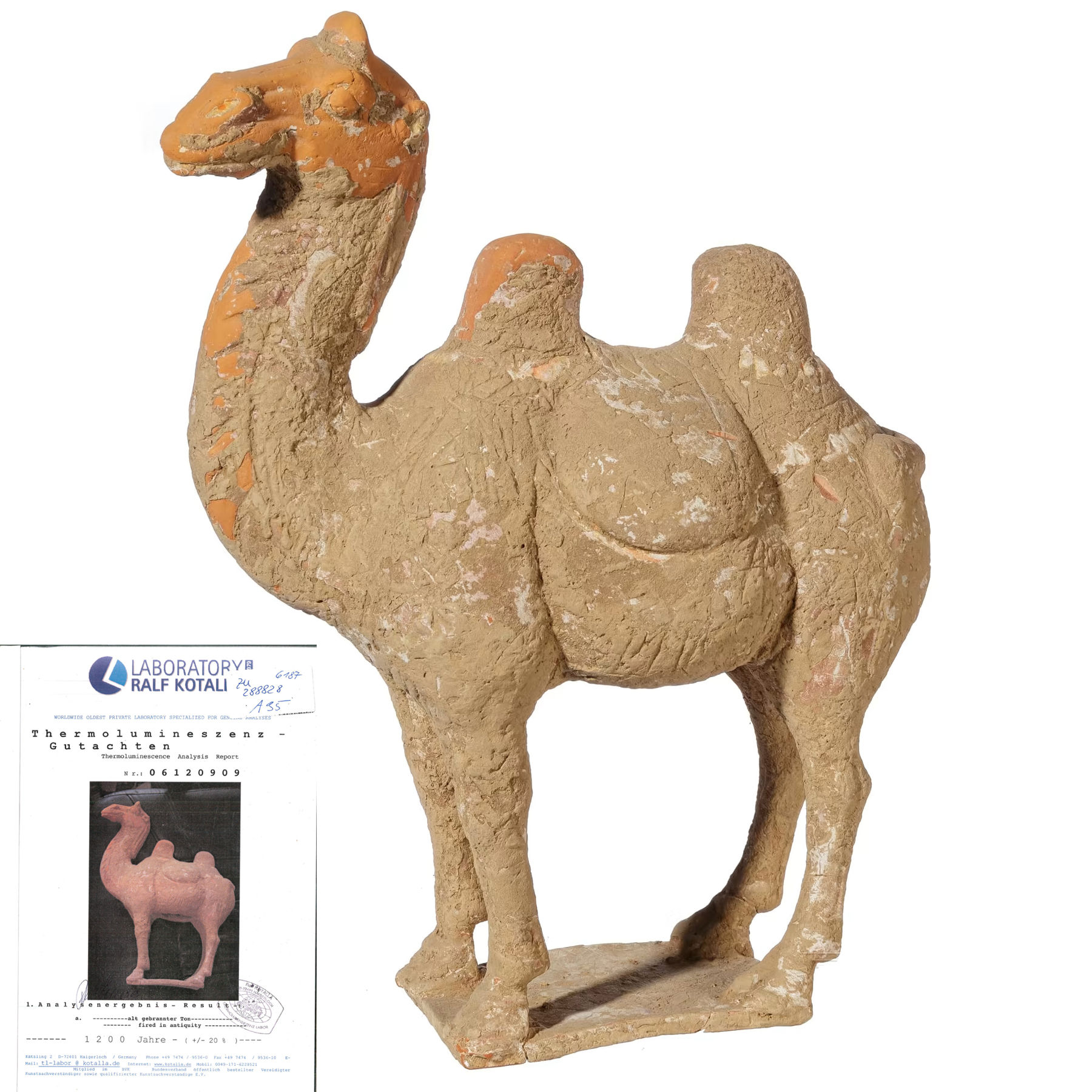

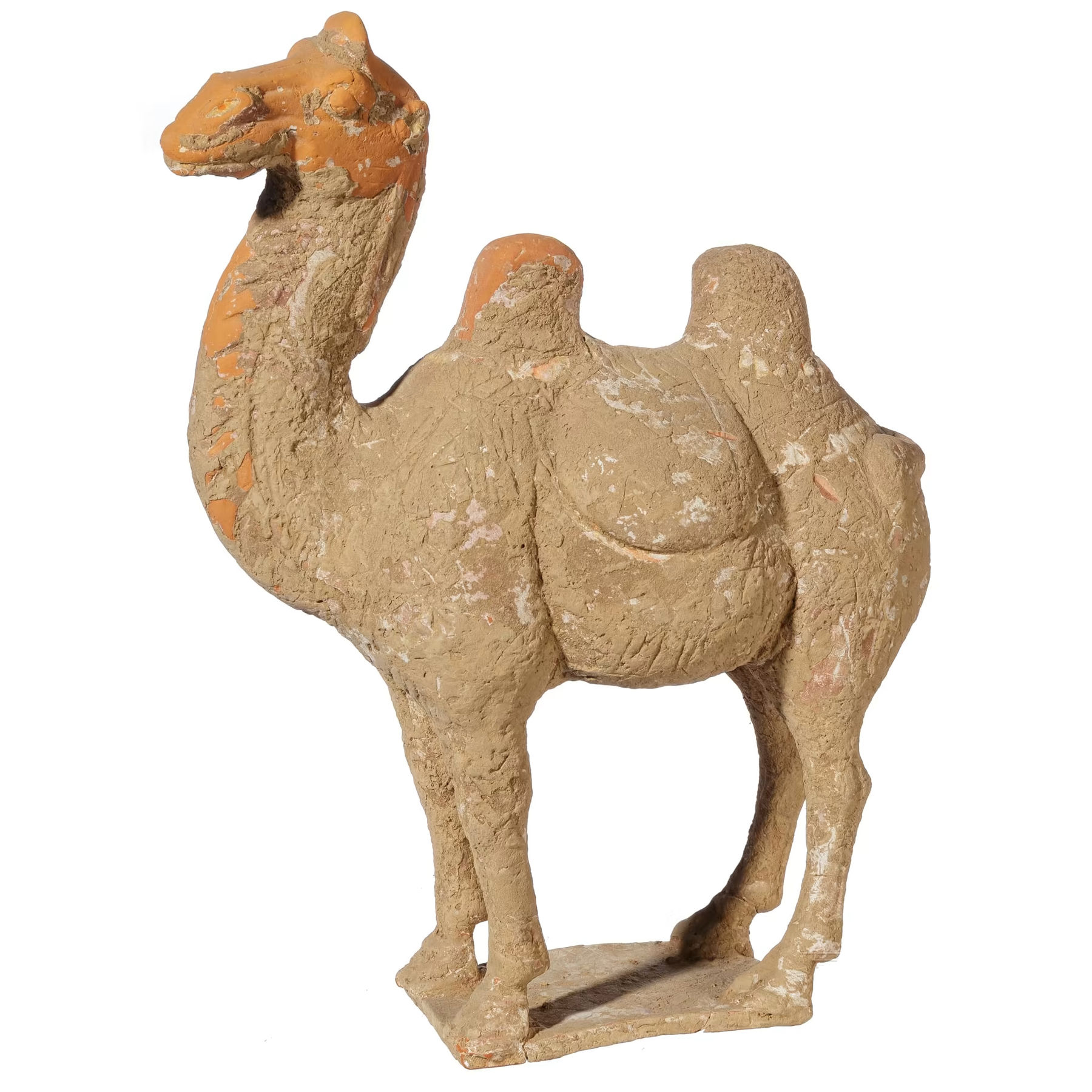

| ITEM | Statuette of a camel |

| MATERIAL | Pottery |

| CULTURE | Chinese, Tang Dynasty |

| PERIOD | 618 – 907 A.D |

| DIMENSIONS | 340 mm x 260 mm |

| CONDITION | Good condition. Includes Thermoluminescence test by Laboratory Ralf Kotalla (Reference 06120909) |

| PROVENANCE | Ex German private collection, acquired before 1990s |

This beautifully-finished ceramic attendant was made during what many consider to be China’s Golden Age, the Tang Dynasty. It was at this point that China’s outstanding technological and aesthetic achievements opened to external influences, resulting in the introduction of numerous new forms of self-expression, coupled with internal innovation and considerable social freedom. The Tang dynasty also saw the birth of the printed novel, significant musical and theatrical heritage and many of China’s best- known painters and artists.

The Tang Dynasty was created on the 18th of June, 618 AD, when the Li family seized power from the last crumbling remnants of the preceding Sui Dynasty. This political and regal regime was long-lived, and lasted for almost 300 years. The imperial aspirations of the preceding periods and early Tang leaders led to unprecedented wealth, resulting in considerable socioeconomic stability, the development of trade networks and vast urbanisation for China’s exploding population (estimated at around 50 million people in the 8th century AD). The Tang rulers took cues from earlier periods, maintaining many of their administrative structures and systems intact. Even when dynastic and governmental institutions withdrew from management of the empire towards the end of the period – their authority undermined by localised rebellions and regional governors known as jiedushi –the systems were so well- established that they continued to operate regardless.

The artworks created during this era are among China’s greatest cultural achievements. It was the greatest age for Chinese poetry and painting, and sculpture also developed (although there was a notable decline in Buddhist sculptures following repression of the faith by pro-Taoism administrations later in the regime). It is disarming to note that the eventual decline of imperial power, followed by the official end of the dynasty on the 4th of June 907, hardly affected the great artistic turnover.

During the Tang Dynasty, restrictions were placed on the number of objects that could be included in tombs, an amount determined by an individual’s social rank. In spite of the limitations, a striking variety of tomb furnishings – known as mingqi – have been excavated. Entire retinues of ceramic figures – representing warriors, animals, entertainers, musicians, guardians and every other necessary category of assistant – were buried with the dead in order to provide for the afterlife. Warriors (lokapala) were put in place to defend the dead, while horses/ camels were provided for transport, and officials to run his estate in the hereafter. Of all the various types of mingqi, however, there are none more elegant or charming than the sculptures of sophisticated female courtiers, known – rather unfairly – as “fat ladies”. These wonderfully expressionistic sculptures represent the idealised beauty of Tang Dynasty China, while also demonstrating sculptural mastery in exaggerating characteristics for effect, and for sheer elegance of execution.

It is likely that the original purpose of the figure was that of a mingqi, terracotta figures designed to be included in a burial in order to accompany the deceased in the afterlife for protection, service and companionship.

They included daily utensils, musical instruments, weapons, armor, and intimate objects such as the deceased’s cap, can and bamboo mat. Mingqi also could include figurines, spiritual representations rather than real people, of soldiers, servants, musicians, polo riders, houses, and horses. Extensive use of mingqi during certain periods may either have been an attempt to preserve the image of ritual propriety by cutting costs, or it may have a new idea separating the realm of the dead from that of the living.

Though these were particularly popular during the Tang dynasty (618-906 AD), mingqi from a broad range of historical periods have been found, with this piece acting as a particularly early example of the practice.

这个精美的陶瓷侍者是在许多人认为是中国的黄金时代–唐朝制作的。正是在这个时候,中国杰出的技术和审美成就向外部影响开放,导致引进了许多新的自我表达形式,再加上内部创新和相当的社会自由。唐朝还诞生了印刷小说、重要的音乐和戏剧遗产以及许多中国最知名的画家和艺术家。唐朝创建于公元618年6月18日,当时李氏家族从之前的隋朝最后的破碎残余中夺取了权力。这个政治和王权政权的寿命很长,持续了近300年。前期和早期唐朝领导人的皇权愿望导致了前所未有的财富,从而使社会经济相当稳定,贸易网络得到发展,并为中国爆炸性的人口(估计在公元8世纪约有5000万人口)带来了巨大的城市化。唐朝统治者借鉴了早期的做法,完整地保留了许多行政结构和制度。即使在这一时期的末期,王朝和政府机构退出了帝国的管理–他们的权威受到了地方叛乱和被称为节度使的地区长官的破坏–这些系统也是如此完善,以至于它们继续运作。

这个时代创造的艺术作品是中国最伟大的文化成就之一。这是中国诗歌和绘画最伟大的时代,雕塑也得到了发展(尽管在政权的后期,亲道教的政府压制了佛教的信仰,佛教的雕塑明显减少)。令人不安的是,皇权的最终衰落,以及907年6月4日王朝的正式结束,几乎没有影响到伟大的艺术更替。在唐朝,对墓葬中可包含的物品数量进行了限制,这一数量由个人的社会等级决定。尽管有这些限制,出土的墓葬陈设–被称为明器–种类惊人。整个陶俑队伍–代表武士、动物、艺人、音乐家、监护人和其他各类必要的助手–都与死者合葬,以便为来世提供服务。战士(lokapala)被安排来保卫死者,而马/骆驼则被提供给运输,官员则在来世管理他的财产。然而,在所有不同类型的明器中,没有比成熟的女朝臣的雕塑更优雅或迷人的了,她们被称为–相当不公平地–“胖女人”。这些精彩的表现主义雕塑代表了中国唐代的理想化之美,同时也展示了雕塑大师为达到效果而夸大特征,以及纯粹的优雅执行。

其最初的用途很可能是明器,是为了陪葬而设计的兵马俑,目的是为了陪伴死者来世的保护、服务和陪伴。

明器包括日常用具、乐器、武器、盔甲,以及死者的帽子、罐子、竹席等私密物品。明器还可以包括士兵、仆人、乐师、马球手、房屋和马匹的塑像、精神代表而非真人。明器在某些时期的广泛使用,可能是为了节约成本,维护礼制的形象,也可能是为了把死人和活人的境界分开的新思想。

唐代的明器虽然特别流行,但各个历史时期的明器都有发现,本件是特别早的例子。