Description

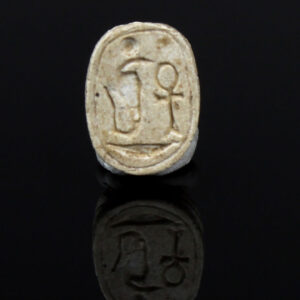

| ITEM | Scarab with solar boat above which a cartouche flanked by two Maat-feathers are depicted. Cartouche of Thutmose III (containing his prenomen “Menkheperre”) |

| MATERIAL | Steatite |

| CULTURE | Egyptian |

| PERIOD | New Kingdom, 1450 – 1300 B.C |

| DIMENSIONS | 15 mm x 10 mm |

| CONDITION | Good condition |

| PROVENANCE | Ex American egyptologist collection, active in the early part of the 20th century, brought to the US with the family in 1954. |

The Egyptians saw the Egyptian scarab (Scarabaeus sacer) as a symbol of renewal and rebirth. The beetle was associated closely with the sun god because scarabs roll large balls of dung in which to lay their eggs, a behavior that the Egyptians thought resembled the progression of the sun through the sky from east to west. Its young were hatched from this ball, and this event was seen as an act of spontaneous self-creation, giving the beetle an even stronger association with the sun god’s creative force. The connection between the beetle and the sun was so close that the young sun god was thought to be reborn in the form of a winged scarab beetle every morning at sunrise. As this young sun god, known as Khepri, rose in the sky, he brought light and life to the land.

Scarab amulets were used for their magical rejuvenating properties by both the living and the dead. Scarabs were used by living individuals as seals from the start of the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055 BCE) onwards. The most common inscription for these scarabs was the owner’s name. The incised design was often a schematic combination of hieroglyphs and geometric patterning. Patterns could often denote the specific administrative office held by the wearer.

Scarabs were also often rendered naturalistically in the round. The regenerative powers of scarabs of this nature could be used by either the living or the dead for healing and protection during quotidian activities or during a deceased person’s passage into the afterlife. The striking red/orange color of this amulet’s carnelian strengthens its solar associations.

Thutmose III (ca. 1479-1425 BC), son of Thutmose II and his secondary wife Isis, was one of the most important kings in Egyptian history. His father died prematurely when he was a child and this led to a regency led by Hatshepsut, the deceased pharaoh’s half-sister and principal wife. Years later, the regent proclaimed herself “king” and would rule Egypt for a long period of time. Little is known about the young prince at the time, although some inscriptions indicate that he was commanding troops to suppress rebels at the end of the period.

Thutmose III had two wives: Satiah and Merytre Hatshepsut, the mother of his successor, Prince Amenophis. His building activity was favoured by his longevity and the amount of wealth Egypt accumulated under his reign. She erected temples all over the country. Politics, ancestors, botany and zoology were his great passions.

After Hatshepsut’s demise, and with little time for the coronation, the young king led the army to crush a coalition of Asian cities and territories at the strategic city of Megiddo. There he achieved a great triumph and designed an ambitious programme of conquest, divided into four phases that included up to sixteen campaigns: occupation of the coasts of Palestine, Lebanon and part of Syria, with the consequent consolidation of positions; attack on the city of Qadesh, whose ruler had been one of the driving forces behind the hostility against Egypt; offensive against the powerful kingdom of the Mitannians, even crossing the Euphrates; and defence of the imperial possessions against uprisings by local rulers and hostile acts by the Mitannians.