Description

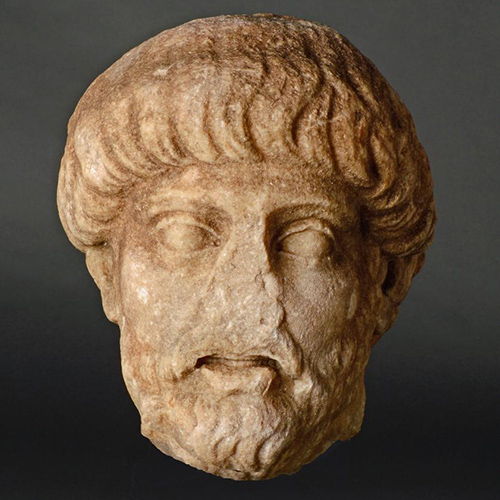

| ITEM | Portrait head of a bearded man, fragment of a sarcophagus |

| MATERIAL | Marble |

| CULTURE | Roman |

| PERIOD | Mid-Second Century A.D |

| DIMENSIONS | 250 mm x 150 mm x 140 mm |

| CONDITION | Good condition, some parts restored by professionals. Includes custom stand |

| PROVENANCE | Ex Austrian private collection (1950 – 1960), Vienna, Ex R. G., Wiener Neustadt, 1988 |

After the long Flavian period (and even that of Trajan, the first emperor of the new dynasty), portrait sculpture underwent a major change with Hadrian.

He introduced the beard (worked with a trephine), which would be maintained by his successors (the Antonine dynasty, such as Marcus Aurelius and Commodus), and a greater idealisation of the portrait.

The gaze changes completely, with the iris emphasised with greater depth (thus creating a more powerful gaze, as Michelangelo would later do in his Moses) and, together with it, a greater closeness to the viewer.

Private portrait sculpture was most closely associated with funerary contexts. Funerary altars and tomb structures were adorned with portrait reliefs of the deceased along with short inscriptions noting their family or patrons, and portrait busts accompanied cinerary urns that were deposited in the niches of large, communal tombs known as columbaria. This funerary context for portrait sculpture was rooted in the longstanding tradition of the display of wax portrait masks, called imagenes, in funeral processions of the upper classes to commemorate their distinguished ancestry.

It is in portraiture that Rome makes its most characteristic contribution to the tradition founded by the Greeks, a contribution that matured much earlier than in other types of sculpture and which caused the development of sculpture in Rome to be divided into two fields, with different patterns of evolution, portraiture and the other types. From the time of the Republic, portraiture was highly valued and over time it oscillated cyclically between an idealising classicist tendency and one of great realism, derived in part from the expressiveness typical of Hellenistic art.

Among the portraits, the bust and head were the most frequent forms. Full-length portraits were less common, although not rare. The preference for the bust and head is a typical Roman cultural trait that created a huge market throughout the Mediterranean basin, and is explained firstly by economic reasons, being much cheaper than a full-length statue, but also by the conviction of a better individual identification that prevailed among them. For the Romans it was the head, and not the body, nor the costumes or accessories, that were the attributes of the centre of interest in the portrait.