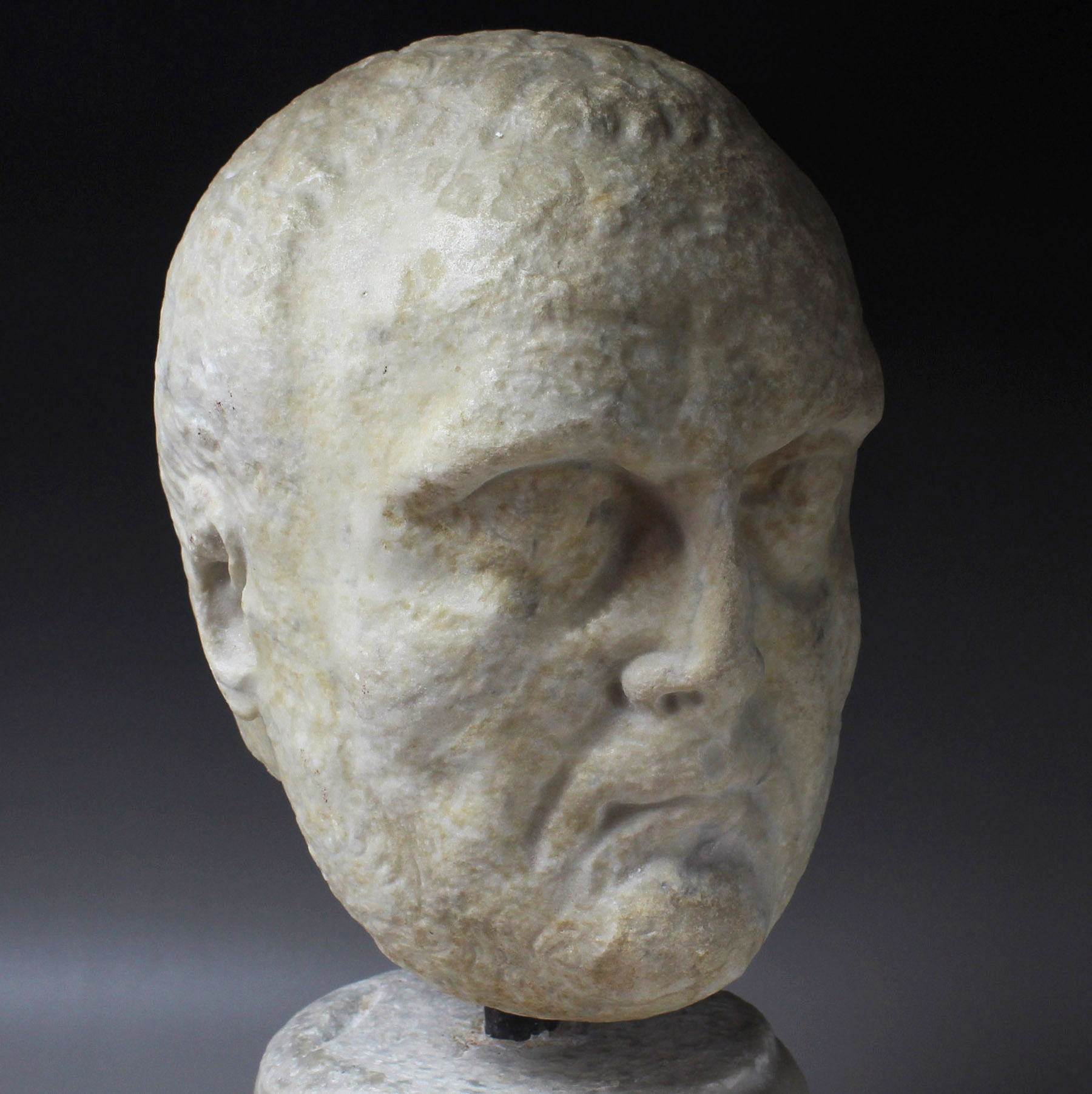

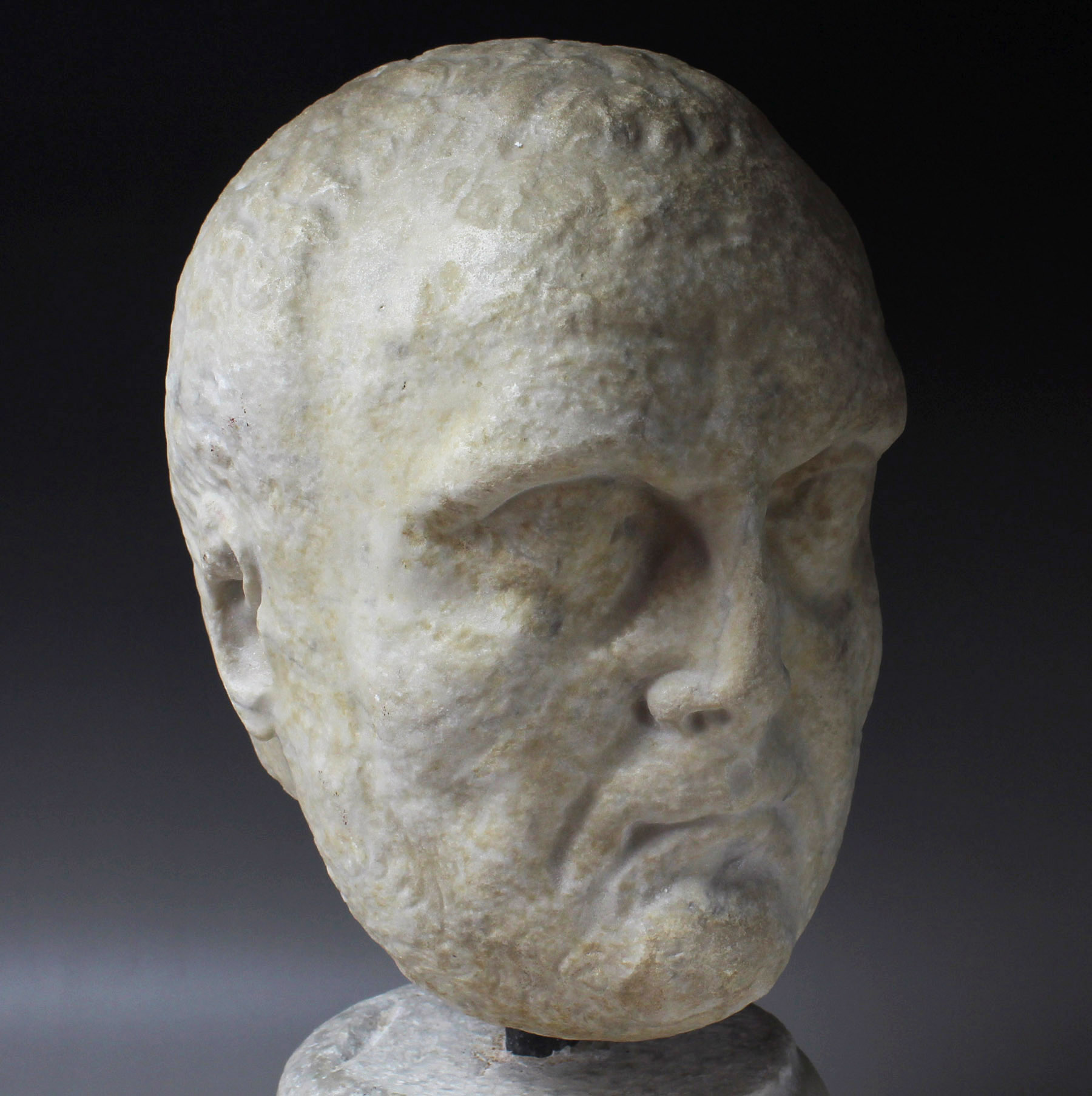

Description

| ITEM | Portrait head of a Patrician |

| MATERIAL | Marble |

| CULTURE | Roman |

| PERIOD | 1st Century B.C |

| DIMENSIONS | 250 mm x 175 mm x 215 mm (without stand), Life-size |

| CONDITION | Good condition. Includes stand |

| PROVENANCE | Ex French private collection, South of France, between the 80’s and 90’s, Ex French private collection of Mr. S., South of France |

During the first century B.C., many men throughout the Mediterranean world chose to be represented in an uncompromisingly realistic manner that accentuated their individual features and the effects of age. This style of portraiture accorded especially well with the austere values of the Roman Republic, which lasted from the fifth century until the late first century B.C.

The traditional Roman concept of virtue called for old-fashioned morality, a serious, responsible public bearing, and courageous endurance in the field of battle. Prestige came as the result of age, experience, and competition among equals within the established political system.

Hyperrealism in sculpture where the naturally occurring features of the subject are exaggerated, often to the point of absurdity. In the case of Roman Republican portraiture, middle age males adopt veristic tendencies in their portraiture to such an extent that they appear to be extremely aged and care worn. This stylistic tendency is influenced both by the tradition of ancestral imagines as well as a deep-seated respect for family, tradition, and ancestry. The imagines were essentially death masks of notable ancestors that were kept and displayed by the family. In the case of aristocratic families these wax masks were used at subsequent funerals so that an actor might portray the deceased ancestors in a sort of familial parade (Polybius History 6.53.54).

The ancestor cult, in turn, influenced a deep connection to family. For Late Republican politicians without any famous ancestors (a group famously known as ‘new men’ or ‘homines novi’) the need was even more acute—and verism rode to the rescue. The adoption of such an austere and wizened visage was a tactic to lend familial gravitas to families who had none—and thus (hopefully) increase the chances of the aristocrat’s success in both politics and business. This jockeying for position very much characterized the scene at Rome in the waning days of the Roman Republic and the Otricoli head is a reminder that one’s public image played a major role in what was a turbulent time in Roman history.